PORTRAIT #03 로잘리 킴 / Rosalie Kim

PORTRAIT #03 로잘리 킴 / Rosalie Kim

로잘리 킴(Rosalie Kim)은 지난 13년간 세계 최대 장식미술관인 빅토리아 앨버트 박물관(V&A)의 한국 미술 큐레이터로 재직해왔다. 로잘리 킴과 엄버 포스트파스트의 인연은 2022년, 그녀가 수석 큐레이터로 기획한 «한류! 코리안 웨이브»(Hallyu! The Korean Wave)의 전시 오프닝에서 엄버의 크리에이티브 디렉터 조성민이 디자인한 드레스를 입으면서 시작되었다. 이 인연은 2024년 빅토리아 앨버트 박물관이 엄버 포스트파스트의 감색 소금 염색 정장을 소장품으로 인수하면서 다시 이어졌다. 로잘리 킴은 독창성보다 교류를 우선시하는 것의 중요성, 그리고 역사 속 사물과 동시대의 오브제를 함께 수집함으로써 ‘시간의 연속성’을 보여주는 것을 강조했다.

PORTRAIT #03 로잘리 킴 / Rosalie Kim

Rosalie Kim has been serving as the curator of Korean Art at the world's largest museum of decorative arts, Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) for the last 13 years. Her relationship with UMBER POSTPAST goes back to when she wore a dress designed by its creative director Jaden Cho at the opening of “Hallyu! The Korean Wave” exhibition, of which she was the lead curator, in 2022. Their paths crossed again when the museum acquired persimmon- and salt-dyed suit made by UMBER POSTPAST in 2024. Kim speaks about the significance of prioritising exchange over uniqueness, and displaying the ‘continuation of time’ by collecting both historical and contemporary objects.

저희 박물관에서는 “한국에서 온 사물은 전부 한국이라는 한 장소에서 온 것”이라고 생각하곤 하는데, 이는 사람들은 한국 내에도 서로 다른 지역이 존재한다는 점을 제대로 이해하지 못하기 때문이에요. 그래서 요즘 저는 지역별 컬렉션을 더 확장하고자 노력하고 있습니다.

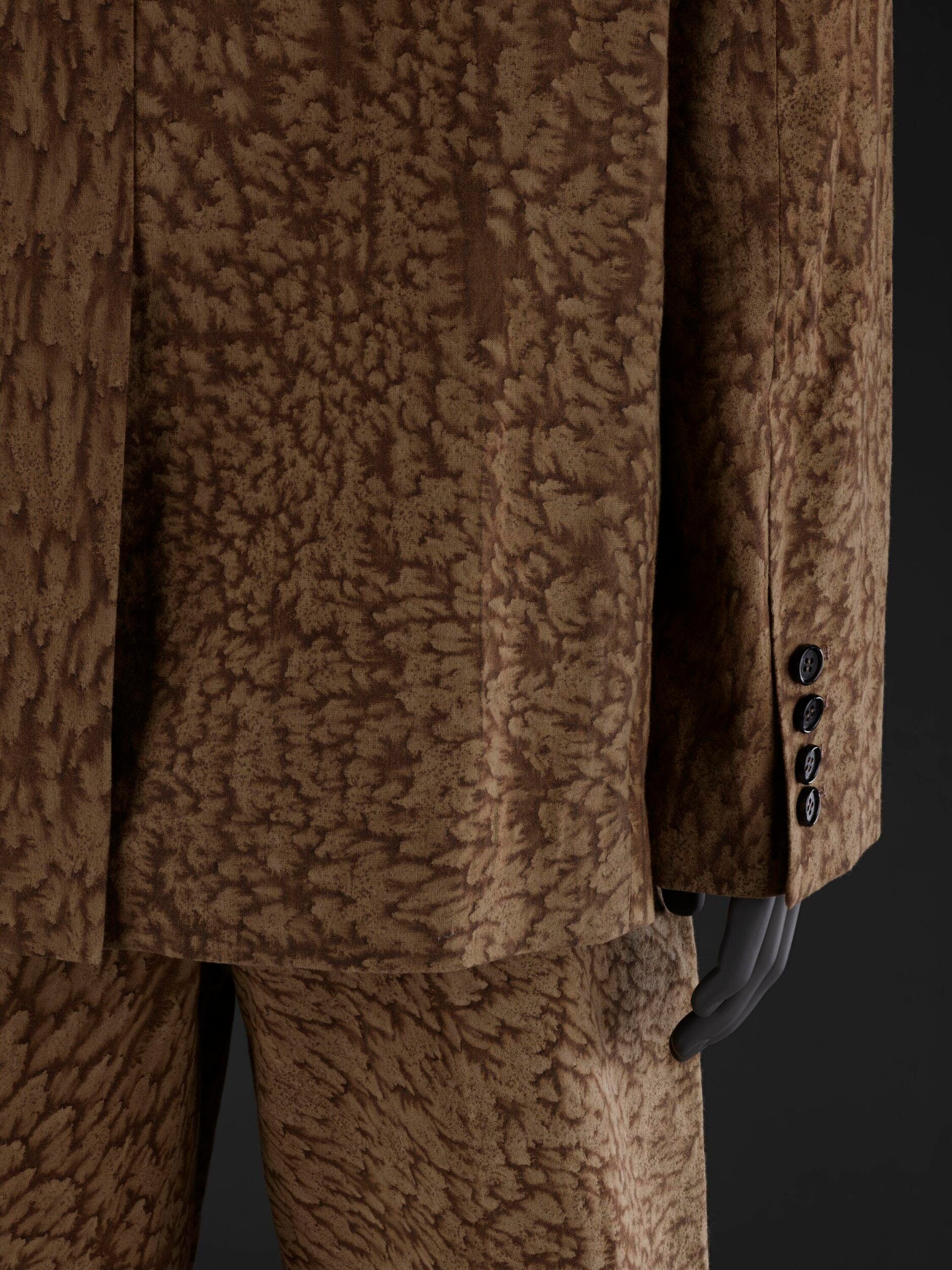

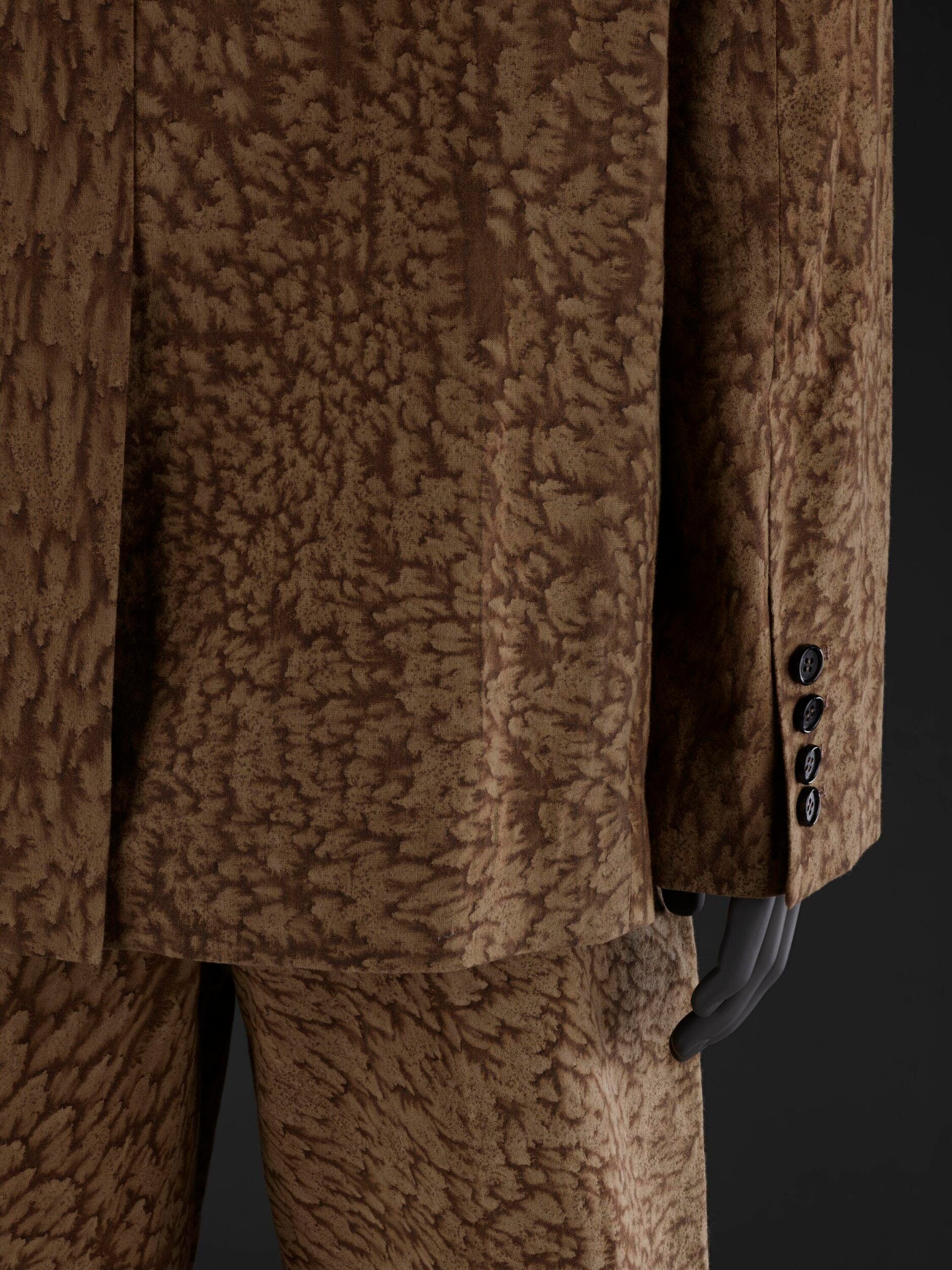

조성민 디자이너의 컬렉션을 살펴보던 중, 마침 ‘소금꽃’ 시리즈가 나왔더라고요. 특히 수트를 포함한 작품들을 봤을 때 매우 현대적이었습니다. 당시 레오파드 프린트가 다시 유행하기 시작하던 시기라, 염색 패턴이 일종의 동물 무늬 같기도 했어요. 저희 컬렉션에서도 이런 작품을 수집하려고자 했는데, 감물 염색한 직물은 대부분 제주도에서 온 것이었어요. 같은 기법을 사용하는 다른 지역이 있다는 사실을 보여줄 수 있다는 점이 흥미로웠습니다. 조성민 디자이너가 설명했듯이, 토양과 기후 때문에 제주도에서 나오던 것과는 다른 색조를 띱니다. 저한테는 이런 지역적 특성이 흥미로웠어요.

There is a tendency in the museum to say things like, “Korean things are all from Korea” and people don't really understand that they are different regions within Korea as well. So I'm trying to see whether we can build more regional collections.

When I was looking at Jaden’s collection, it just happened that the latest thing was the salt flower series. When I saw the pieces, especially the suit, it was very modern. It was, at the time, when leopard print was coming to the fore again and it looked kind of like an animal print pattern. We had been pursuing those objects in our collection, but most of them are from Jeju Island. It was interesting to show that there are other regions working with the same technique. As Jaden was explaining, because of the soil and the climate, it has a different shade of color than those you might find elsewhere, like in Jeju. I felt like these kinds of regionalities were interesting.

제가 이해하기로는 일본 감 염색 방식은 한국 감 염색 방식과 다릅니다. 타닌 함량과 관련이 있는 것으로 알고 있는데, 일본산에서는 걸러진 성분이 한국산에는 걸러지지 않아 색조가 달라집니다. 그러니까 둘 다 감을 사용하지만 구성 성분이 다른 것이에요. 이를 명확히 하려면 과학적 분석이 필요하겠죠.

동아시아를 넘어선 사례를 보는 것도 흥미로울 것 같아요. 중동 지역이나 감이 자라는 다른 지역에서는 감을 다르게 활용했을 수 있죠. 혹은 다른 과일을 사용하더라도 색상은 유사하거나, 같은 재료를 사용해도 기술적 접근이 달랐을 수도 있습니다. 세계 다른 지역에서 이런 직물이 유통되며 새로운 영향을 촉발한 사례가 있었을까? 아시아 내 다른 지역, 즉 남아시아, 동남아시아, 오세아니아와의 관계는 어땠을까? 이런 질문들을 탐구하고자 하는거죠.

From my understanding, the way the Japanese persimmon dye works is different from the way Korean persimmon dye does. It's something to do with the level of tannin, but there is an element that is filtered out in the Japanese one, which is not in the Korean one, and so you get different hues. So despite the fact that they are both using persimmon, they are different in composition; we'll have to do a scientific analysis to be able to define that.

It’s also interesting to see beyond East Asia. There might be other ways of using persimmon in the Middle East, or in other countries where you have this type of fruit. Or they have different types of fruit but the same sort of quality in terms of colors maybe, or different in terms of their technique. Was there any sort of sale of those types of fabrics elsewhere in part of the world, that then went on to trigger something else? What was the relationship with other regions within Asia, with South Asia, Southeast Asia, Oceania? Those are also the questions that we're looking at.

빅토리아 앨버트 박물관은 대영제국 역사상 특정 시기에 설립된 박물관이에요. 영국 갤러리를 제외하면 아시아 부서가 유일한 지역별 부서입니다. 물론 여기에는 장단점이 있어요.

한 편으로는 한국 미술 컬렉션처럼 상대적으로 소규모 컬렉션을 별도의 갤러리로 운영하면, 저희 박물관처럼 방대한 세계적 소장품 속에서 존재감이 사라지는 것을 방지할 수 있어요. 반면 일본, 중국, 한국, 인도 갤러리를 따로 두면 해당 컬렉션들의 '타자성'이 부각됩니다. 이름을 보는 순간 관람객은 바로 “아, 저건 다른 나라의 것”이라고 생각하게 되어, 의식적이든 무의식적이든 자동적으로 다른 방식으로 인식하는 것이에요. 요즘처럼 민족주의가 고조되는 세상에서는 이게 항상 좋은 것만은 아닙니다. 문화는 늘 유동적이었으며, 두 나라를 연결하는 외교적 통로 역할을 해왔다는 것을 강조해야하니까요. 초창기 한국 갤러리의 서사는 “한국은 독특하다”, “한국은 중요하다”였습니다. 물론 한국은 중요하고 독특합니다. 그 점을 부정하는 건 아니에요. 하지만 그런 전시 방식의 문제점은 세계와의 연결고리를 잃어버린다는 점입니다. 19세기에 생긴 '은둔의 왕국'이라는 개념을 부각시키는데, 이는 당시 한국을 방문한 적도 없는 미국 작가가 만들어낸 완전히 서구적인 개념입니다. “한국인은 이렇다, 저렇다”라고 말함으로써 당시 일어났던 문화 교류에 대해 이야기하지 않게 되고, 한국을 다른 나라들과 동등한 위치에 놓지 않게 됩니다. 그래서 저는 동시대 자료와 역사적 자료, 대량 생산된 물건과 예술 작품, 무형유산과 산업적으로 생산된 것을 함께 전시하기 시작했어요. 이를 통해 사람들이 한국의 물질문화에 대해 다시 생각해보게 하려는 거죠. 한국 역사나 문화의 빛나는 면모는 고려나 조선 시대에만 머물러 있지 않잖아요. 사실 전통은 오늘날까지 이어지고 있으며, 특히 공예와 디자인 분야에서 빛나고 있어요.

We are in a museum that was established during a specific time in British Empire history. And aside from the British galleries, the Asian department is the only geographical department. This has its pros and cons.

On the one hand, having a separate gallery for a relatively smaller collection like the Korean collection prevents it from disappearing in a global museum and its vast collections. On the other hand, having galleries of Japan, China, Korea, or India would emphasize the otherness of those collections. You’d think, “Oh, that's a different country,” so you automatically set yourself in a different sort of mental state, consciously or unconsciously. I suppose in a world where nowadays nationalism is growing, this isn’t always really a good thing because you want to say that culture is always on the move and it has always been a diplomatic channel to bring two nations together. Now, I think in the Korea Gallery, the narrative initially was “Korea is unique,” “Korea is important.” And it is; I'm not saying that it's not important, that it's not unique. But my problem with that kind of presentation is that it loses contact with the rest of the world. And it almost emphasizes the 19th-century idea of ‘hermit kingdom,’ which is a concept that was written by an American author who never, at the time of penning that, traveled to Korea. So it's a completely Western concept. And by saying “oh, Koreans are this, Koreans are that,” you don't talk about the sort of cultural exchanges that happened during that time; you don't situate Korea on par with others. So I started displaying contemporary materials with historical materials, mass-produced materials with artistic materials, things made by living national treasures with things made in industries, to have people re-think about Korean objects. The brilliance of Korean history or culture doesn’t solely reside in the Goryeo Dynasty or Joseon Dynasty, but actually these traditions continue to this day, and you can see nowadays—especially with craft and design—that they are coming to the fore as well.

최근 한국에 계신 몇몇 분들께 1960년대나 70년대에 할머니가 입었던 옷이 있는지 수소문을 하기 시작했어요. 전시할 수 있는 작품의 범위를 넓히기 위해서였죠. 서양 박물관의 관점에서 보면 일부 디자인이 특별히 신선하거나 새롭지 않을 수 있어 어려운 일이기도 해요. 박물관 측에서는 왜 그런 작품들을 수집해야 하는지 이해하지 못하는 경우도 있습니다. 하지만 당시 문화적 맥락이라든지, 서양 디자인과 미묘하게 다른 점 같이 고려가 필요한 측면들도 있습니다. 그래서 한국의 초기 디자이너들의 작품도 더 많이 수집하려고 노력하고 있어요. 이 글을 읽는 분들 중 이런 물건을 소장하고 계신데 기증할 의향이 있으신 분이 계시다면 연락주세요. (웃음)

많은 사람들이 어떤 것이 한국만의 독특한 것인지, 일본만의 독특한 것인지, 중국만의 독특한 것인지를 정의내리려 노력하곤 합니다. 하지만 이 '독특함'이라는 개념은 때로 오해의 소지가 있습니다. 항상 긍정적인 의미만은 아니기 때문이죠. 다른 사람들이 따라 하지 않았다면, 그것은 곧 아무에게도 영향을 주지 못했다는 뜻입니다. 다른 이들에게 영감을 주지 못했다는 거죠. 저는 무언가가 독특하지 않을 때 오히려 좋다고 생각합니다. 즉 그 무언가가 세계적인 대화의 장의 일부였다는 뜻이며, 그것이 속한 문화와 배경을 통해 대화에 기여했다는 의미이기 때문이에요. 이건 긍정적인 거에요. 인류 역사의 일부이자, 전 세계적 문화 교류의 일부였다는 거잖아요. 요즘은 다들 자신의 문화와 그 경계를 지나치게 소중히 여긴다고 생각해요. 다른 이들에게 영감을 주기도 하고, 다른 이들에게서 영감을 받기도 하면서 동시에 그것을 자기 자신의 것으로 만들었다고 할 수 있다는 건 정말 멋진 일이라고 생각합니다.

Actually we have made a call recently asking a few people in Korea if they had clothes that their grandmother used to wear from the 1960s or the 70s, so that we can expand the range of things we can show. This is also difficult, because from a Western museum perspective, some of the designs might not be amazingly fresh or new. So the museum sometimes doesn't really understand why they should acquire those. But then there are other aspects, such as what the cultural context was at the time and why they are slightly different from Western designs. So we're trying to make more collections of those early designers as well. If anybody in Korea reads this and has amazing things and they would like to donate, we are very open to this.

People are constantly trying to think if something is unique to Korea or unique to Japan or unique to China. But this concept of uniqueness is sometimes misleading because it's not always a good one. If you don't see other people doing it, then it means it didn't affect anybody, you know. It didn't inspire anybody else to do this. I think it's nice, when something’s not necessarily unique. Because it means that you are part of the whole discussion around the world and you made a contribution to that with your own culture and your own background. So it's a good thing. That's part of human history, that's part of the whole global exchange of culture. And it’s revealing that nowadays, everybody is just precious about their boundaries, their culture. I think it's nice to be able to say that actually you inspired others, you were inspired by others, but you made it yours as well.

PORTRAIT #03 로잘리 킴 / Rosalie Kim

로잘리 킴(Rosalie Kim)은 지난 13년간 세계 최대 장식미술관인 빅토리아 앨버트 박물관(V&A)의 한국 미술 큐레이터로 재직해왔다. 로잘리 킴과 엄버 포스트파스트의 인연은 2022년, 그녀가 수석 큐레이터로 기획한 «한류! 코리안 웨이브»(Hallyu! The Korean Wave)의 전시 오프닝에서 엄버의 크리에이티브 디렉터 조성민이 디자인한 드레스를 입으면서 시작되었다. 이 인연은 2024년 빅토리아 앨버트 박물관이 엄버 포스트파스트의 감색 소금 염색 정장을 소장품으로 인수하면서 다시 이어졌다. 로잘리 킴은 독창성보다 교류를 우선시하는 것의 중요성, 그리고 역사 속 사물과 동시대의 오브제를 함께 수집함으로써 ‘시간의 연속성’을 보여주는 것을 강조했다.

PORTRAIT #03 로잘리 킴 / Rosalie Kim

Rosalie Kim has been serving as the curator of Korean Art at the world's largest museum of decorative arts, Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) for the last 13 years. Her relationship with UMBER POSTPAST goes back to when she wore a dress designed by its creative director Jaden Cho at the opening of “Hallyu! The Korean Wave” exhibition, of which she was the lead curator, in 2022. Their paths crossed again when the museum acquired persimmon- and salt-dyed suit made by UMBER POSTPAST in 2024. Kim speaks about the significance of prioritising exchange over uniqueness, and displaying the ‘continuation of time’ by collecting both historical and contemporary objects.

저희 박물관에서는 “한국에서 온 사물은 전부 한국이라는 한 장소에서 온 것”이라고 생각하곤 하는데, 이는 사람들은 한국 내에도 서로 다른 지역이 존재한다는 점을 제대로 이해하지 못하기 때문이에요. 그래서 요즘 저는 지역별 컬렉션을 더 확장하고자 노력하고 있습니다.

조성민 디자이너의 컬렉션을 살펴보던 중, 마침 ‘소금꽃’ 시리즈가 나왔더라고요. 특히 수트를 포함한 작품들을 봤을 때 매우 현대적이었습니다. 당시 레오파드 프린트가 다시 유행하기 시작하던 시기라, 염색 패턴이 일종의 동물 무늬 같기도 했어요. 저희 컬렉션에서도 이런 작품을 수집하려고자 했는데, 감물 염색한 직물은 대부분 제주도에서 온 것이었어요. 같은 기법을 사용하는 다른 지역이 있다는 사실을 보여줄 수 있다는 점이 흥미로웠습니다. 조성민 디자이너가 설명했듯이, 토양과 기후 때문에 제주도에서 나오던 것과는 다른 색조를 띱니다. 저한테는 이런 지역적 특성이 흥미로웠어요.

There is a tendency in the museum to say things like, “Korean things are all from Korea” and people don't really understand that they are different regions within Korea as well. So I'm trying to see whether we can build more regional collections.

When I was looking at Jaden’s collection, it just happened that the latest thing was the salt flower series. When I saw the pieces, especially the suit, it was very modern. It was, at the time, when leopard print was coming to the fore again and it looked kind of like an animal print pattern. We had been pursuing those objects in our collection, but most of them are from Jeju Island. It was interesting to show that there are other regions working with the same technique. As Jaden was explaining, because of the soil and the climate, it has a different shade of color than those you might find elsewhere, like in Jeju. I felt like these kinds of regionalities were interesting.

제가 이해하기로는 일본 감 염색 방식은 한국 감 염색 방식과 다릅니다. 타닌 함량과 관련이 있는 것으로 알고 있는데, 일본산에서는 걸러진 성분이 한국산에는 걸러지지 않아 색조가 달라집니다. 그러니까 둘 다 감을 사용하지만 구성 성분이 다른 것이에요. 이를 명확히 하려면 과학적 분석이 필요하겠죠.

동아시아를 넘어선 사례를 보는 것도 흥미로울 것 같아요. 중동 지역이나 감이 자라는 다른 지역에서는 감을 다르게 활용했을 수 있죠. 혹은 다른 과일을 사용하더라도 색상은 유사하거나, 같은 재료를 사용해도 기술적 접근이 달랐을 수도 있습니다. 세계 다른 지역에서 이런 직물이 유통되며 새로운 영향을 촉발한 사례가 있었을까? 아시아 내 다른 지역, 즉 남아시아, 동남아시아, 오세아니아와의 관계는 어땠을까? 이런 질문들을 탐구하고자 하는거죠.

From my understanding, the way the Japanese persimmon dye works is different from the way Korean persimmon dye does. It's something to do with the level of tannin, but there is an element that is filtered out in the Japanese one, which is not in the Korean one, and so you get different hues. So despite the fact that they are both using persimmon, they are different in composition; we'll have to do a scientific analysis to be able to define that.

It’s also interesting to see beyond East Asia. There might be other ways of using persimmon in the Middle East, or in other countries where you have this type of fruit. Or they have different types of fruit but the same sort of quality in terms of colors maybe, or different in terms of their technique. Was there any sort of sale of those types of fabrics elsewhere in part of the world, that then went on to trigger something else? What was the relationship with other regions within Asia, with South Asia, Southeast Asia, Oceania? Those are also the questions that we're looking at.

빅토리아 앨버트 박물관은 대영제국 역사상 특정 시기에 설립된 박물관이에요. 영국 갤러리를 제외하면 아시아 부서가 유일한 지역별 부서입니다. 물론 여기에는 장단점이 있어요.

한 편으로는 한국 미술 컬렉션처럼 상대적으로 소규모 컬렉션을 별도의 갤러리로 운영하면, 저희 박물관처럼 방대한 세계적 소장품 속에서 존재감이 사라지는 것을 방지할 수 있어요. 반면 일본, 중국, 한국, 인도 갤러리를 따로 두면 해당 컬렉션들의 '타자성'이 부각됩니다. 이름을 보는 순간 관람객은 바로 “아, 저건 다른 나라의 것”이라고 생각하게 되어, 의식적이든 무의식적이든 자동적으로 다른 방식으로 인식하는 것이에요. 요즘처럼 민족주의가 고조되는 세상에서는 이게 항상 좋은 것만은 아닙니다. 문화는 늘 유동적이었으며, 두 나라를 연결하는 외교적 통로 역할을 해왔다는 것을 강조해야하니까요. 초창기 한국 갤러리의 서사는 “한국은 독특하다”, “한국은 중요하다”였습니다. 물론 한국은 중요하고 독특합니다. 그 점을 부정하는 건 아니에요. 하지만 그런 전시 방식의 문제점은 세계와의 연결고리를 잃어버린다는 점입니다. 19세기에 생긴 '은둔의 왕국'이라는 개념을 부각시키는데, 이는 당시 한국을 방문한 적도 없는 미국 작가가 만들어낸 완전히 서구적인 개념입니다. “한국인은 이렇다, 저렇다”라고 말함으로써 당시 일어났던 문화 교류에 대해 이야기하지 않게 되고, 한국을 다른 나라들과 동등한 위치에 놓지 않게 됩니다. 그래서 저는 동시대 자료와 역사적 자료, 대량 생산된 물건과 예술 작품, 무형유산과 산업적으로 생산된 것을 함께 전시하기 시작했어요. 이를 통해 사람들이 한국의 물질문화에 대해 다시 생각해보게 하려는 거죠. 한국 역사나 문화의 빛나는 면모는 고려나 조선 시대에만 머물러 있지 않잖아요. 사실 전통은 오늘날까지 이어지고 있으며, 특히 공예와 디자인 분야에서 빛나고 있어요.

We are in a museum that was established during a specific time in British Empire history. And aside from the British galleries, the Asian department is the only geographical department. This has its pros and cons.

On the one hand, having a separate gallery for a relatively smaller collection like the Korean collection prevents it from disappearing in a global museum and its vast collections. On the other hand, having galleries of Japan, China, Korea, or India would emphasize the otherness of those collections. You’d think, “Oh, that's a different country,” so you automatically set yourself in a different sort of mental state, consciously or unconsciously. I suppose in a world where nowadays nationalism is growing, this isn’t always really a good thing because you want to say that culture is always on the move and it has always been a diplomatic channel to bring two nations together. Now, I think in the Korea Gallery, the narrative initially was “Korea is unique,” “Korea is important.” And it is; I'm not saying that it's not important, that it's not unique. But my problem with that kind of presentation is that it loses contact with the rest of the world. And it almost emphasizes the 19th-century idea of ‘hermit kingdom,’ which is a concept that was written by an American author who never, at the time of penning that, traveled to Korea. So it's a completely Western concept. And by saying “oh, Koreans are this, Koreans are that,” you don't talk about the sort of cultural exchanges that happened during that time; you don't situate Korea on par with others. So I started displaying contemporary materials with historical materials, mass-produced materials with artistic materials, things made by living national treasures with things made in industries, to have people re-think about Korean objects. The brilliance of Korean history or culture doesn’t solely reside in the Goryeo Dynasty or Joseon Dynasty, but actually these traditions continue to this day, and you can see nowadays—especially with craft and design—that they are coming to the fore as well.

최근 한국에 계신 몇몇 분들께 1960년대나 70년대에 할머니가 입었던 옷이 있는지 수소문을 하기 시작했어요. 전시할 수 있는 작품의 범위를 넓히기 위해서였죠. 서양 박물관의 관점에서 보면 일부 디자인이 특별히 신선하거나 새롭지 않을 수 있어 어려운 일이기도 해요. 박물관 측에서는 왜 그런 작품들을 수집해야 하는지 이해하지 못하는 경우도 있습니다. 하지만 당시 문화적 맥락이라든지, 서양 디자인과 미묘하게 다른 점 같이 고려가 필요한 측면들도 있습니다. 그래서 한국의 초기 디자이너들의 작품도 더 많이 수집하려고 노력하고 있어요. 이 글을 읽는 분들 중 이런 물건을 소장하고 계신데 기증할 의향이 있으신 분이 계시다면 연락주세요. (웃음)

많은 사람들이 어떤 것이 한국만의 독특한 것인지, 일본만의 독특한 것인지, 중국만의 독특한 것인지를 정의내리려 노력하곤 합니다. 하지만 이 '독특함'이라는 개념은 때로 오해의 소지가 있습니다. 항상 긍정적인 의미만은 아니기 때문이죠. 다른 사람들이 따라 하지 않았다면, 그것은 곧 아무에게도 영향을 주지 못했다는 뜻입니다. 다른 이들에게 영감을 주지 못했다는 거죠. 저는 무언가가 독특하지 않을 때 오히려 좋다고 생각합니다. 즉 그 무언가가 세계적인 대화의 장의 일부였다는 뜻이며, 그것이 속한 문화와 배경을 통해 대화에 기여했다는 의미이기 때문이에요. 이건 긍정적인 거에요. 인류 역사의 일부이자, 전 세계적 문화 교류의 일부였다는 거잖아요. 요즘은 다들 자신의 문화와 그 경계를 지나치게 소중히 여긴다고 생각해요. 다른 이들에게 영감을 주기도 하고, 다른 이들에게서 영감을 받기도 하면서 동시에 그것을 자기 자신의 것으로 만들었다고 할 수 있다는 건 정말 멋진 일이라고 생각합니다.

Actually we have made a call recently asking a few people in Korea if they had clothes that their grandmother used to wear from the 1960s or the 70s, so that we can expand the range of things we can show. This is also difficult, because from a Western museum perspective, some of the designs might not be amazingly fresh or new. So the museum sometimes doesn't really understand why they should acquire those. But then there are other aspects, such as what the cultural context was at the time and why they are slightly different from Western designs. So we're trying to make more collections of those early designers as well. If anybody in Korea reads this and has amazing things and they would like to donate, we are very open to this.

People are constantly trying to think if something is unique to Korea or unique to Japan or unique to China. But this concept of uniqueness is sometimes misleading because it's not always a good one. If you don't see other people doing it, then it means it didn't affect anybody, you know. It didn't inspire anybody else to do this. I think it's nice, when something’s not necessarily unique. Because it means that you are part of the whole discussion around the world and you made a contribution to that with your own culture and your own background. So it's a good thing. That's part of human history, that's part of the whole global exchange of culture. And it’s revealing that nowadays, everybody is just precious about their boundaries, their culture. I think it's nice to be able to say that actually you inspired others, you were inspired by others, but you made it yours as well.